Powerhouse Museum curator Eva Czernis-Ryl responds to Material Language in the exhibition catalogue essay.

I hope you see these pots when the sun is out. They quicken with light.

– Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, 2005

My first encounters with Prue Venables’ ceramics, Nadège Desgenetez’s glass sculptures and Joungmee Do’s metalwork are deeply etched in my memory. Why is it that when we handle objects created by human hands our touch tends to linger and we so easily become enchanted? Bringing together a remarkable selection of some of the finest works from these three artists, globally renowned for their outstanding skill, material knowledge and artistic achievements, this captivating exhibition sheds light on reasons behind those moments of enchantment, and more broadly, behind the prominent place these practitioners occupy on the Australian arts and design scene.

Although these artists create with different materials, tools and processes, they have much in common. They have developed their long and successful careers by working with demanding materials traditionally reserved for male practitioners. Their work explores dual qualities of strength and fragility, that yin and yang of physical presence and etherealness that each artist balances so admirably. While the strength quality comes from material knowledge, that certain fragility stems from each artist entrusting their chosen material to map her soul.

When interviewed in 2022 about challenges she faced during the Covid-19 pandemic when not able to make glass and travel, Nadège Desgenetez’s response revealed how deeply she identified with her practice: ‘More than a method or a means of executing my ideas, glass blowing for me is a way of finding self, of knowing, of worlding. It helps me connect ideas, people and places. Through Covid I was confronted with how much I relied on it to find ground.’ Originally from France and now moving between Melbourne and Canberra, Nadège ‘unwillingly fell’ for the ancient tradition of glass blowing because of its relationship to time and unique experience of embodied presence. She embraced the challenges of the material’s contrasting abilities to be fluid when hot and solid and strong when cold but always courting its propensity to shatter. Noting that women did not begin to blow glass at the furnace until the late 1960s, she highlights how her commitment to rigorous technical approach and pushing the boundaries of glass were deemed rare, when she began working with some of the most renowned international glassblowers in the 1990s. As an artist holding a set of self-titled ‘eclectic and somewhat anachronistic skills set’ she wills her work to speak to the relevance of the hand and handmade in our fast-paced, screen dominated times. At the time of the Covid-19 interview, Nadège had been developing her mirrored glass sculptures for a decade. These ambiguous works reference the human body merged with elements of the Australian landscape. Inspired by the artist’s migrant story, they explore experiences of connection to place, of interrelation with the world, but also of longing, and disconnection. The scale of these abstracted forms demands a heightened physical connection with the work. Over time, Nadège has become more attuned to the demands and opportunities of the process and how the molten glass is shaped by touch and breath in a sequence that requires not only a keen awareness of her body’s boundaries, but also of the physicality of those working with her in large teams. Her sculptures demand expert hands across many processes. Whilst echoing a modernist nod to fragmented classical sculptures, Nadège’s works move from the classical masculinity of white marble. Her enigmatic body fragments hold an appearance of her breath containers. Covered with silvered membranes and reflecting – in fairground-mirror fashion – the changing world around them, they seem anchored by the precious cargo they bear yet ready to break away from their existence like party balloons. These works are the artist’s tribute to the vessels we live in, and our ever-changing experiences of the world we belong to.

The Korean-Australian jewellery and metalwork artist Joungmee Do has to practise daily to maintain dexterity of her hands. ‘If I don’t practise even for a day, my hands tell me I’ve been lazy,’ she explains. It is mesmerising to watch her at work in her studio as she demonstrates the traditional Korean technique, her trademark, called ipsa (jjoeumipsa). Methodically and with utter precision, centimetre by centimetre, she strikes metal surface with hammer and chisel four times in different directions – parallel, vertical and diagonally. Some 350 hammer blows are required for one centimetre square, just as she learned from master Choe Kyo-jun. Once she is satisfied with that luxuriously velvety texture, she inlays it with a thread-like 0.15 mm silver wire. Joungmee credits traditional Korean fabrics, particularly wrapping cloths (bojagi), as an inspiration behind the delicacy of her surface patterns. But it is the challenges and rewards of shaping the material, the contrasting properties of metal – coldness and warmth (when worked) – that drive experiment, fierce perseverance and her growth as an artist.

Drawing on both Korean and Western cultures, Joungmee belongs to the cohort of predominantly female Korean artists living abroad who have played a key role in both the preservation and reimagining of Korean metal craft that suffered a complete demise in the first half of the 20th century during Korea’s tragic history that saw Japanese occupation, World War II, Soviet and American occupation and eventually the three-year Korean War from 1950. Trained in Korea and at Melbourne’s RMIT, she has now lived in Australia for 27 years. In her insightful essay about Korean metal craft, Powerhouse curator Min-Jung Kim, highlights the term jang-in (master of craft) traditionally used in Korea to recognise people devoted to practising a particular skill to become masters of their chosen profession. She advocates for this term to be considered beyond traditional frameworks and extended to denote contemporary artists from across the globe who demonstrate exceptional, whole-hearted commitment to craft practice and who use their hands, minds and hearts to make works that are their ‘other self’.

The artists in this exhibition are contemporary jang-ins. In fact, Prue Venables, whose practice spans over four decades of working with ceramics from studios in Australia and London, UK, is a recipient of the Australian jang-in award: The Living Treasure: Masters of Australian Craft, an honour bestowed by the Australian Design Centre. Prue first studied zoology, while her creative side found an outlet in passion for music and flute playing. Pottery followed with intense decades of experimentation and technical knowledge building, grounded in strong work ethic. In 1991 Prue’s ceramic world transformed again: she first touched Limoges porcelain. She refers to that experience of working with this stunningly white and versatile material as her ‘point of recognition… like a musical basso ostinato, this became the foundation for imaginative learning – the discovery of new processes and expression. The practice that I subsequently developed has become intrinsic to me, inseparable, and an important vehicle for exploring the interior landscape of myself.’

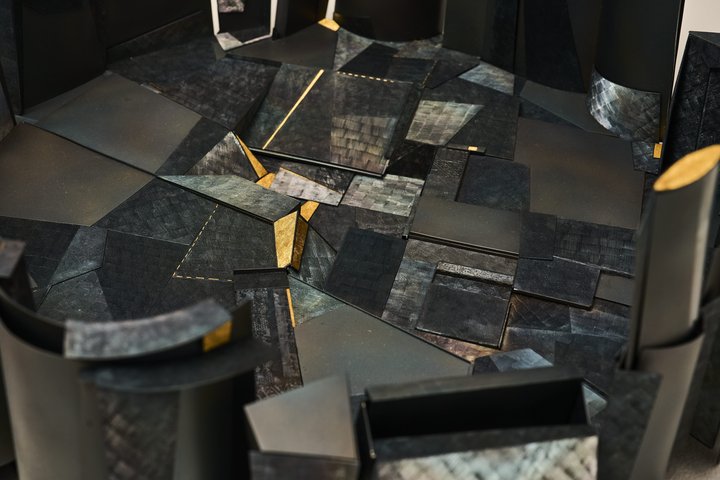

One ‘look’ is never enough when we are in the presence of Prue’s nonchalantly intriguing ceramics; ‘This work so artfully combines stillness and a sense of risk, of fragility… [these are] slightly perverse groupings that quietly and insistently demand a shift in our perception,’ wrote Gwyn Hansen Piggott. With their wheel-turned forms slightly altered, circles gently reshaped, Prue’s slightly anthropomorphic vessels are in perpetual conversation amongst themselves. There is always a line: soaring then tamed, maybe it is the first thing you see. A lip contour, loud then quiet, you must trace it with your finger. Black forms bowing, inviting, never too far from coolly elegant white beings congregating in changing formations. The more recent works as seen in this exhibition, are more radically altered, from the round-bodied into further fresh and unexpected identities. While metal, a new component material, facilitates unanticipated forms, new colours energise space, objects hide and expose each other playfully. ‘Form and concept dance, settled and resolved at times, and then, at others, playing with the discomfort of the unexpected.’ In concert with their Material Language glass and metal companions, these objects dance to the heartbeat of the maker.

Eva Czernic-Ryl is an art and design historian, author and award-winning curator at Powerhouse Museum in Sydney.