There's an assumed knowledge in my household that if something has gone missing, my mother probably donated it. My dad and my five siblings have grown so accustomed to this behaviour over the years that we no longer get mad about it. We instead fault ourselves for not hiding things better.

My mother's journey into minimalism began in her childhood home. She was the solitary female presence among four brothers, and it was her responsibility to clean the house while her immigrant parents worked. Cleaning in my grandmother's home is no easy feat. To this day, her home continues to accumulate an ever-expanding inventory of furniture, crockery and trinkets. Plenty of new things make their way into my grandparents' abode, but nothing ever leaves. While my grandmother, someone who has been diagnosed with severe OCD, might be classified as a hoarder, her home defies the chaotic stereotypes often portrayed in mainstream media. In her world, everything possesses its designated spot - a sanctuary for ribbons she has kept from gift wrapping, a haven for pins, batteries and buttons, repurposed shoe boxes for storage, etc. Chances are, if you needed something, my grandmother probably has it stashed somewhere neatly, and she knows precisely where that item can be found and whether or not it has moved - even a few centimetres out of place. My mother, on the other hand, has sculpted her approach to belongings under the guiding philosophies of minimalist YouTubers and the wisdom imparted by Marie Kondo: "if it doesn't spark joy, let it go". She has done a lot of letting go in her lifetime on behalf of the whole family.

I have spent considerable time alongside these two influential women in my life: my mother, with whom my bond is naturally profound, and my grandmother, whom I travelled with to our motherland of Lebanon and also lived with during lockdown, offering her companionship and care. Somewhere between my grandmother's attachment to and my mother's detachment from material possessions, I've formed my own relationship with stuff. A middle ground where items are not just joy sparkers but objects with embodied energy that simply donating or throwing away is often unjustified. I try to think more thoughtfully about what I purchase and if it's possible to find a secondhand alternative before buying something new. I've learned to nurture a balanced, thoughtful relationship with the objects that surround me.

This relationship was enhanced by the knowledge I gained through my bachelor's degree in Fashion Design and Technology at RMIT. I learnt about the textile supply chain and realised that each phase of garment production involves some form of environmental harm or human rights exploitation. I couldn't reconcile with participating in an industry that continually exacerbates the production of clothing, especially when there is already an abundance of garments that could sustain us without the necessity of fabricating anything new. Instead, I have become obsessed with revitalising old or overlooked garments and other objects that seemed to have lost their charm, and I fell in love with the art of machine embroidery. This space allowed me to create without perpetuating the cycle of disposable fashion. I learnt the skill during my undergraduate degree and later invested in a semi-industrial embroidery machine. This machine transformed into more than just a tool - it became a beacon of renewal, enabling me to salvage objects that might have otherwise ended up in landfills. This practice was not limited to clothing; it extended to various found objects, encompassing handkerchiefs, towels, met cards, and even skateboards. Through my efforts, these items were not only saved from oblivion but reborn, challenging the norms of a society prone to diminishing sentimentality and the perceived value in objects.

These days, I operate my embroidery ventures on the side while dedicating a significant portion of my time to a Master of Architecture at Monash University. I was lucky enough to join a program at the University that accommodates students from various undergraduate backgrounds to shift into this 3-year course. The large-scale nature of architecture has always captivated me, especially the necessity to create structures that either stand the test of time or have a defined end-of-life purpose.

As my graduation approaches, I am focused on embarking on a career that specialises in adaptive reuse, with the aspiration to breathe new life into dilapidated buildings. I anticipate that my foundation in fashion design will significantly influence my architectural creations. A distinct synergy between the two disciplines has become apparent to me, and I eagerly journey the path that integrates the finesse of textiles with the dynamics of space.

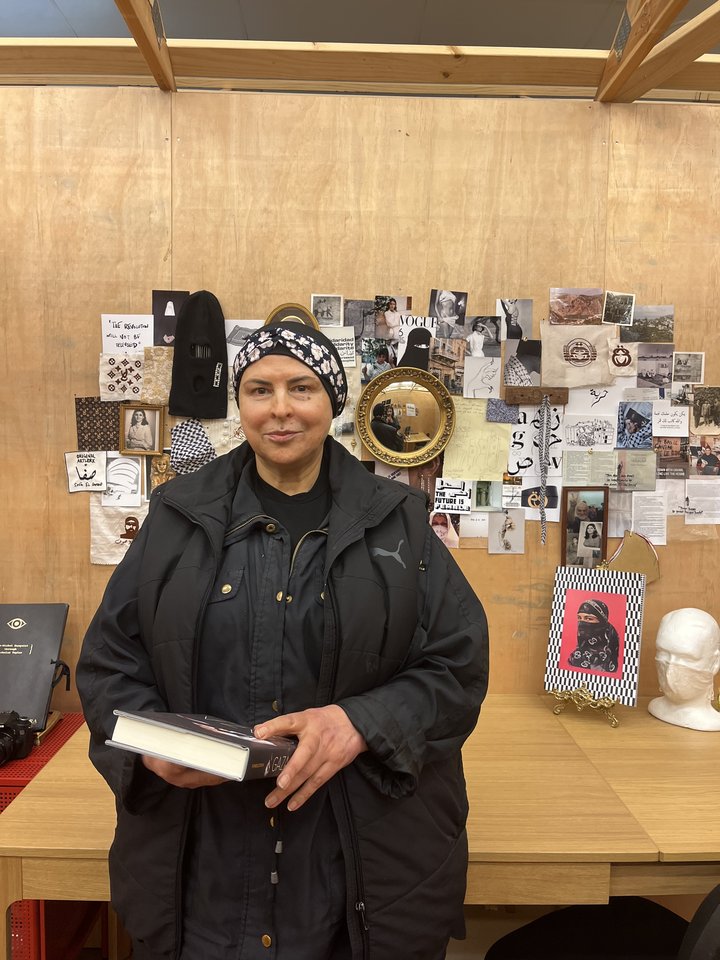

Safa El Samad is a second-generation Lebanese Australian, who lives by the axiom that ‘the architect should be able to design everything from the city to the spoon.’ Not only a testament to her all-rounded experience as a multidisciplinary artist and fashion designer, Safa is also passionate about art and design that is built to last. Recently she designed the 9th Mpavilion uniforms. She is currently completing a Masters of Architecture at Monash University in Melbourne Australia.